Rethinking wOBA, xwOBA, xERA, and Stuff+

I’ve been working on sxwOBA, a baseball statistic that aims to model expected hitting outcomes based on the exit velocity, launch angle, spray direction, and batter sprint speed of a given batted-ball event. The metric was inspired by the statcast metric xwOBA which contrastingly leaves out spray angle.

As baseball savant notes:

“Expected Outcome stats help to remove defense and ballpark from the equation to express the skill shown at the moment of batted ball contact.”

Taking this approach helps us remove some of the noise and factors that are outside of the batter or pitcher’s control for a more robust performance estimation. Aditionally, wOBA and xwOBA are context-neutral, so baserunner state and number of outs are controlled for and hitters are credited with the relative run value of the plate appearance based on linear weights. The use of linear weights creates consistency by valuing different offensive outcomes—like walks, singles, and home runs—based on their average historical impact on scoring runs. These metrics credit players based on the inherent value of their performance, independent of the specific game situation. So, a home run is valued the same whether it’s a solo shot or a grand slam because these stats aim to evaluate the hitter’s skill, not their luck of having runners on base.

Why wOBA is overrated

If you look closely at the wOBA equation, you’ll notice that it only credits hitters for positive outcomes, such as walks or hits. All outs are treated the same, they simply add to the denominator, with no change to the numerator.

But let’s take a step back for a second and think about double plays. They are treated the same as a single out because any events where the batter does not get on base are treated the same (+0 to the numerator, +1 to the denominator). If all outs are credited the same, then the latent assumption here is that avoiding double plays is not a real skill, which is obviously false because hitters greatly vary in their launch angle distribution and ground ball frequencies. This is a major issue because wOBA and its variations are used in some of the most commonly used stats in the baseball community. wRC+, xwOBA, and xERA all inherit this bias from wOBA.

For some players this bias is negligible, for others it is substantial. It really just depends how much of an outlier the player is in terms of their frequency of double plays. A hitter who grounds into many double plays will be less productive than their wOBA indicates, and a hitter who grounds into few double plays will be more productive than their wOBA indicates. On average, double plays decrease run expectancy by a massive amount–about -0.85 runs on average which is almost three times that of a single out. With the best groundball pitchers typically accumulating about 20-25 double plays per seasons, this adds up in a major way.

Now, wOBA is mainly an offensive stat, but it has been adapted to evaluate pitchers in several different cases and they also fail to take into account double plays. Baseball savant’s expected ERA (xERA) takes a pitcher’s xwOBA and and puts it on an ERA scale so that we can get a better picture of run prevention skill with respect to contact quality.

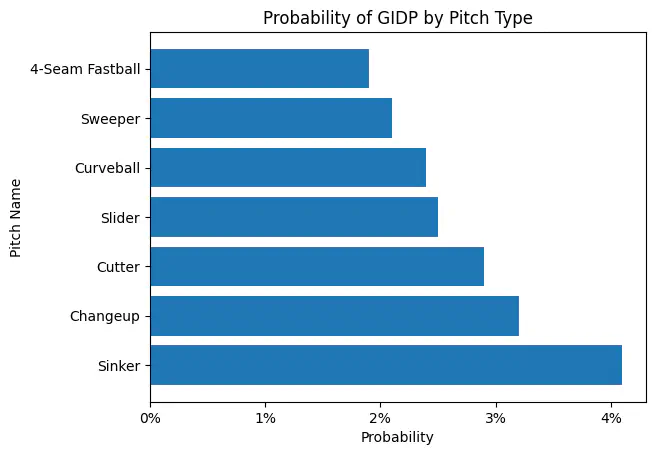

Similarly, using wOBA to measure the effectiveness of different pitch types results in the undervaluing of pitches like sinkers and changeups, which more often result in double plays. As a result, some have even written off sinkers as a dying pitch citing lopsided wOBA figures without realizing that the main strength of the pitch was not being taken into account.

This problem extends to stuff quality models as well. These metrics evaluate pitches based on their expected run value (xRV) by learning how pitches of similar characteristics (velocity, movement, release position, etc) perform. However, run value isn’t a very well-defined metric in the sabermetrics community–there are different ways of calculating it with different levels of granularity and some important tradeoffs to take into account with each. The main differencs lie in how situational outs are treated.

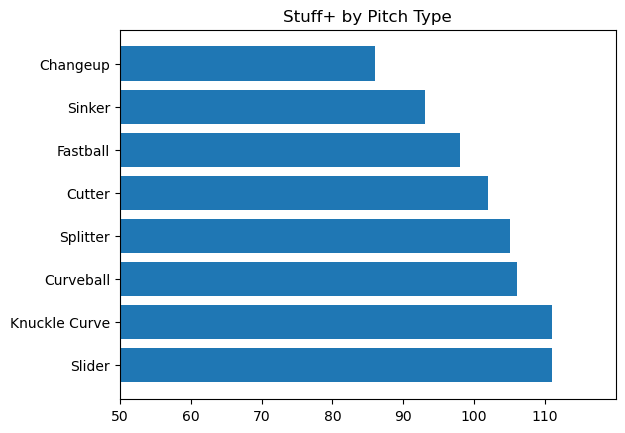

The simple method, which is used in Stuff+, uses linear weights like the ones used in wOBA and treats all outs as equal to remain context-neutral. That means double plays, force outs, and sacrifice flies get replaced with the run value of a single out. This reduces some of the noise in run values so that we reward the pitcher based on how the pitch would perform in most scenarios, rather than situationally. But this really isn’t the right way to go about things. Pitchers have a fair amount of control over the launch angle of their balls in play. Pitchers who get more ground balls will induce more double plays in the long run. These pitchers will also be more adept at avoiding sacrifice flies by keeping the ball out of the air more often. These discrepancies help explain why sinkers and changeups are so poorly rated by Stuff+.

Another method for computing run values is to treat situational outcomes like double plays, force outs, and sacrifice flies as unique outcomes to be assigned their own linear weights. This method is of course not fully context-neutral because these outcomes depend on the situation. However it still remains context neutral on outcomes like singles, doubles, triples, homeruns, walks, and strikeouts by crediting these outcomes based on their average run value.

Finally, there is the context-specific version of run values. This is the version you will find on baseball-savant, which factors in the value of the play with respect to baserunners and outs. While this method is good at describing pitchers’ actual run prevention performance, it should not be used in stuff quality models because it suffers from noise due to luck in situational ability much like ERA can be noisy due to a lower or higher than average strand rate (LOB%).

Each of these three methods have their own advantages and drawbacks, and I don’t think any of them are quite optimal if we are trying to create a well-calibrated stuff quality metric. Instead, I’ll propose two alternative methods that should in theory do a better job while remaining context neutral.

The first is to credit groundouts and airouts differently. We can group ground ball double plays with other ground ball outs and calculate the average run value of these outcomes separately from air outs. As a result, ground ball outs will be weighted slightly more valubale than air outs (which includes line drives and fly balls) due to the increased chance of a double play and decreased chance of a sacrifice fly. This method keeps things simple; it remains context neutral, but more accurately describes the value of each outcome.

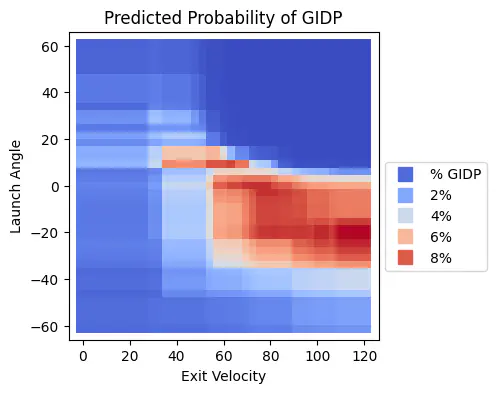

The second method is a bit more technical to implement, but would go even further to reduce noise and improve our performance estimation. Instead of examining the actual outcomes, we can generate probability estimates of each possible outcome based on variables like launch angle, exit velocity, and spray direction. Using expected outcomes would remove some of the luck that is inherent with evaluating the actual outcomes. For example, think of a situation where a ground ball is hit to the shortstop. Let’s say based on the batted ball characteristics that 40% of the time similar batted balls turn into singles, another 40% of the time it turns into an out, and the last 20% it turns into a double play. We can then calculated the expected run value of that batted ball by taking the weighted sum of the run values of each of the three potential outcomes. If a pitcher had a season where they were particularly unlucky with ground balls hit just past the reach of the shortstop, the model would take that into account. This is especially important for outlier pitches. For any machine learning model, the general principle is that more data leads to better performance. This is because small samples tend to be more noisy, so if we have an outlier pitch with little data for the model to generalize on, any reduction in noise of that sample can help us improve the calibration of our estimand.

In a future article, I plan to delve deeper into these different run value implementations to pinpoint the most accurate method for capturing baseball’s intricate scenarios. While metrics like wOBA, xwOBA, xERA, and Stuff+ have significantly enhanced our grasp of player performance, there’s always room for improvement. By incorporating nuances such as double plays and situational outcomes, we can do a better job evaluating players and generating accurate predictions of performance for hitters and pitchers alike.